Digital Assets Part 2: Safeguarding Access to Digital Assets

Part 1 of this series on digital assets explored some of the more popular types of digital assets and accounts that you should consider when planning for incapacity and death. In this entry, we will look at how these accounts are governed under current law and give some practical tips that can help you ensure that your fiduciaries and family can access your digital assets when they need to.

Terms of Service Agreements

Every online service is governed by a Terms of Service Agreement (TOSA) that you agree to when you create an account and begin using the site. There is a good chance that you skipped past those terms when you set up your account—after all, you just wanted to watch The Mandalorian, not read a contract!

Cumbersome as they may be, Terms of Service Agreements are important to understanding your rights as a user of the platform, and often contain terms that outline what should happen to your account if it goes unused for a long time or you die. Some accounts allow fiduciaries to access the full contents of the account, while others consider the entry of a third party—even a duly designated fiduciary—as a breach of the user agreement. It is important that you review the terms of your most important accounts to understand what steps are required for a fiduciary to have access to your data.

Terms of Service Agreements are designed to work within existing law and may be updated from time to time by the provider.

Online Tools

Most people have multiple online accounts or assets, which means they have multiple Terms of Service Agreements to balance. To make it easier for the average consumer to control their accounts, laws have been adopted in most states that allow users to determine what should happen with their digital assets and electronic communications, and with whom that information should be shared.

The Florida Fiduciary Access to Digital Assets Act was passed in 2016 to grant fiduciaries the legal authority to manage digital assets and electronic communications and give providers guidance on how to interact with fiduciaries while keeping the promises of privacy that they made to users. The Act can be read in its entirety at Chapter 740 of the Florida Statutes.

The Act introduced the idea of “online tools,” defined as “an electronic service provided by a custodian which allows the user . . . to provide directions for disclosure or nondisclosure of digital assets to a third person.” Section 740.002(16), Florida Statutes. These tools exist outside of the Terms of Service Agreement for a product or platform and, if completed by the user, tell the provider what information they would like to share and who should receive that information. If a provider does not offer an online tool, the terms of a power of attorney, will, or other estate planning documents may grant the fiduciary access to the information.

Most major online providers offer an online tool to their users. The following are a few examples of major platforms or providers and how they incorporate online tools in their products.

Facebook allows users to choose between designating a “legacy contact” that can look after a user’s “memorialized” account after the user’s death or opting to have the account permanently deleted once Facebook learns of the user’s death. Users can access the online tool to make their selection by visiting their profile settings.

Google’s suite of products—including Gmail, Google Drive, and YouTube—offer a unified “Inactive Account Manager” that allows users to delete their account upon death or designate a “trusted contact” to receive an alert when the account is inactive for a certain amount of time. You might use this tool to make sure that any future guardians or personal representatives know of your Google Account and can access the data stored in it.

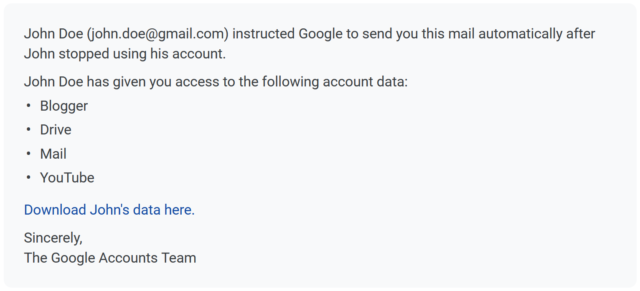

Google’s tool allows users to pick which information in their account (if any) is to be shared with the trusted contact. If the account remains inactive for a while, the trusted contact receives an email from Google with a link to download your data. This email might look like this:

Apple

On the other hand, the world’s largest tech company, Apple Inc., does not provide an online tool to allow users to designate a fiduciary’s access to their accounts. Apple is well-known for their hard stance on privacy and is reluctant to allow anything that might compromise a user’s account. In most cases, Apple requires a court order before it will agree to release a user’s data or communications. This makes it all more important to make alternative arrangements for management of Apple accounts after death, such as leaving passwords in a safe place for loved ones to find.

Passwords & Authorized Users

There are other paths to protecting access to your data outside of online tools. Some accounts permit “authorized users” (different platforms have different names for them), which allow approved people to access your purchases and, in some cases, your data and communications (if you choose). An example of this is Apple’s “Family Sharing” feature, which allows a user to share their purchases and subscriptions with members of their family. Some portals allow multiple accounts to manage the same property, such as multiple authorized users on an online banking platform.

If an account does not allow you to designate an authorized user or recipient of your data (with an online tool), you might consider leaving your passwords where fiduciaries and family can find them if they ever need to. Another option to consider is using a password manager, such as LastPass, 1Password, or Dashlane. Password managers store your passwords for individual accounts and allow you to log in to any site or account using a single master password. This solution can make things more convenient for you now and guarantee your fiduciaries can access your accounts in the future.

You should never leave passwords in estate planning documents. Your will, trust, power of attorney, or other estate files may become public or be viewed by people other than your fiduciary and family.

Two-Factor Authentication

A final and important note on passwords: be wary of two-factor authentication. Two-factor authentication has been around for decades but has recently become a widespread tool that adds a second layer of security onto accounts protected by a password. When you use two-factor authentication, you receive a randomly-generated pin—usually via text message—that you must enter after logging in with a password. This provides an extra guarantee that the person accessing the site is in fact the user, since you must have both the password and access to the user’s phone.

You may only have to complete two-factor authentication once on your device, so you may not be aware that two-factor authentication is enabled for your accounts. You should check your security settings to see if it is enabled.

On the practical side, this means your fiduciaries must have access to your phone to access your accounts. You should leave your phone’s passcode with your other passwords so that fiduciaries can bypass two-factor authentication. Just a friendly reminder, though: fiduciaries and family members should never impersonate you if they access your accounts, even with your permission—it may violate the Terms of Service Agreement for that account.

Disposing of Electronic Devices

Our gadgets and devices can be quite valuable. If you own a smartphone, tablet, laptop, e-reader, smartwatch, smart TV, and their accessories, you have likely spent nearly $5,000 on hardware alone, not to mention the services that go along with them. It makes sense that you would want to gift these pieces of property to family and friends when you die. You paid good money for them—someone ought to get some use out of them.

However, disposing of modern electronic devices is not as straightforward as making a gift in your will—security features in these devices may add an extra step before they are gifted, donated, or sold.

For example, Apple products come with a feature called “Activation Lock,” which is enabled by default for most users. When enabled, that specific device is tied to your Apple ID, even if you reset the device to its factory settings. You must enter your Apple ID password to disable Activation Lock before another user can set up the phone. Failing to disable Activation Lock may “brick” your phone, making it inaccessible (and therefore, useless). Apple can bypass Activation Lock in some circumstances but may choose not to do so. Disabling Activation Lock saves a lot of time and trouble and—if a court order is required for Apple to unlock the device—money.

Activation Lock is exclusive to Apple devices, but Android- and Windows-based devices from Google, Samsung, LG, Microsoft, and others may offer a similar feature. Failing to provide the passcode for your phone and the password for the account tied to your phone might render them useless to later users, whether beneficiaries or buyers.

Part 3: Coming Soon

In our final entry in this series, we will discuss some of the ways your estate plan can consider digital assets and ways you and your attorney can ensure that they remain accessible to your guardian, agent, personal representative, and family.

Would you like more help navigating digital asset protection in your estate plan? Contact us today.